Good Feeding Practices

10 Rules of Horse Feeding

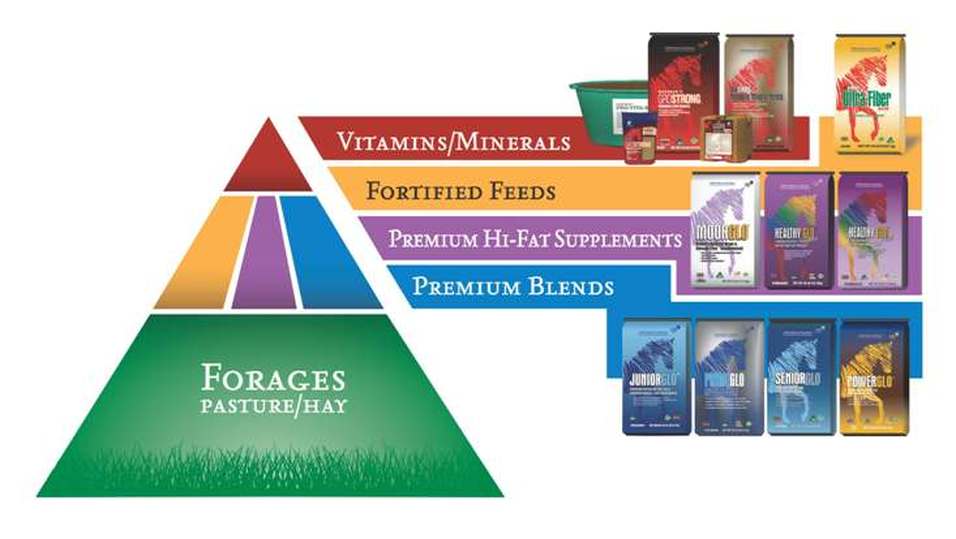

Equine Food Pyramid:

|

6. Feed according to size, work, breed, temperament, age and time of year

|

Hay

|

There is a lot of controversy among horse owners about which hay cutting is best. Hay quality depends largely on type, growing conditions and how it was harvested/stored. The fiber content of hay (often found in the stalks) increases as it grows, while the protein content (most prominent in the leaves) diminishes. The leaves grow out first, following by the development of a bud which later blooms and eventually seeds. Usually hay is cut during the late bud or early bloom phase to maximize nutritional value. However, growing conditions can interfere with this such as wet Spring weather delaying the harvest of first cutting. While all cuttings can result in great horse hay, depending on the variables just discussed, there are some consistent differences between first and second cutting. First cut is generally noted for being higher in fiber (takes longer to chew and digest, which is advantageous in the winter), but may have a fairly high weed content. Second cutting is clean, soft, green and palatable. It often has a higher protein content and overall nutritional value, but is digested faster. All of these things make second cutting better suited for pregnant mares, show horses or hard-keepers who need an easy and quick caloric intake. This higher protein and calorie content can be too much for some horses, resulting in lameness or obesity. In conclusion, a good quality first cutting of hay is usually perfectly adequate for the average adult horse and is actually preferred in the winter.

TIP: Even though we all try to pick the best quality hay possible, it is likely

to still be a little dusty. Studies have shown that ingestion of dust is less harmful the inhalation. Therefore, dusty hay can be soaked in water to help remove some dust particle. What isn't rinsed away, will stick to the hay, which is still preferred over having it in the air. Excessive soaking can result in nutrient loss, so hay should only be soaked for 10 minutes. However, soaking hay for a longer period of time can reduce carbohydrate content when desirable, such as for insulin resistant horses who are shown to have an increased risk of Equine Metabolic Syndrome, Obesity, and Laminitis (19,43). |

Good-quality hay is usually bright green in color (indicating a high level of vitamin A) and smells fresh/sweet. Hays that are pale green or tan may simply be bleached and are often still good quality. Brown hay, however, indicates a loss of nutrients due to excessive water and heat damage and should be avoided (Hill, 2000). Do not feed hay that smells moldy, dusty, sour or rancid. Not only is it unpalatable but dusty hay can contribute to respiratory diseases while the toxic fungal spores in mold have been linked to colic and abortions. * Also be careful to avoid Alfalfa with blister beetles, as even 5 grams of these 1/2 inch long toxic (contain cantharidin) insects can kill a horse. Common symptoms of cantharidin poisoning include depression, decreased appetite, abdominal pain and increased urination, but can only be confirmed with laboratory testing. You may think you've found a great deal on hay but it's not a good deal if your horses won't eat it or it makes them sick so always check the quality and try a test bale or look elsewhere when in doubt!

Hay types fall into two categories: grasses (such as timothy and orchard) and legumes (most commonly alfalfa). Grass hay alone is adequate for most adult horses. Combining Alfalfa and grass hay can be beneficial for growing horses who need the additional protein in their diet. It is not advisable to feed exclusively Alfalfa, due to the excessive protein the horse will receive and the high Ca:P ratio. Other, less commonly fed, types of forage include silage (highest moisture content) and haylage (in between silage and hay).

It is important to store hay in a dry environment, ideally in a building seperate from the barn (due to the risk of spantaneous compustion and their general flamability). If this is not an option, many barns have storage available in a loft above the stalls. Filling the loft, however, can be a tiring and tedious task. Investing in a hay elevator or paying someone to deliver your hay is often well worth the cost for what it saves you in time, energy and general wear and tear on your back. Smaller quantities, used for more immediate feeding, can be stored in wide aisle-ways or spare stalls. If it is absolutely necessary to store you hay outside, place them on pallets and wrap in a tarp. This is important to prevent spoilage from both the sun and the rain.

It is important to store hay in a dry environment, ideally in a building seperate from the barn (due to the risk of spantaneous compustion and their general flamability). If this is not an option, many barns have storage available in a loft above the stalls. Filling the loft, however, can be a tiring and tedious task. Investing in a hay elevator or paying someone to deliver your hay is often well worth the cost for what it saves you in time, energy and general wear and tear on your back. Smaller quantities, used for more immediate feeding, can be stored in wide aisle-ways or spare stalls. If it is absolutely necessary to store you hay outside, place them on pallets and wrap in a tarp. This is important to prevent spoilage from both the sun and the rain.

Grain

It is important to store grain in a cool, dry place. Grains do expire and should therefore be fed as soon after being purchased as is practical. All grains spoil more quickly during hot, humid weather. Cracked and rolled grains go bad faster than whole grains. Sweet feeds can not only turn rancid easily, but the molasses forms hard clumps that are difficult to scoop when the weather is cold. Sometimes moldy grain has white or black coating on it but when in doubt, trust your nose. Moldy corn, for example, appears completely normal and yet contains an incredibly toxic fungus called Fusarium moniliform which can cause severe neurological disorders.

Having a designated "feed room" with a concrete floor and door is ideal. Store loose grain or opened bags in plastic storage barrels with tight-fitting lids, to protect it from insects and rodents. If you have barn-cats and therefore are not concerned about rodents, you can place grain anywhere the horses can't access it. This is incredibly important because, if a horse were to gain access to a grain room, he would binge on feed, most likely colic and possibly even die. When grain bins are stored outside or in a garage, you may need to install a locking latch to keep raccoons and bears out. If your barn floor is dirt, it is important to use pallets to keep the bags of grain off the cool, moist ground. Another option is to build a large wooden feed bin directly against a wall, to store loose/bagged/barreled grain as well as scoops and buckets.

Tips:

Having a designated "feed room" with a concrete floor and door is ideal. Store loose grain or opened bags in plastic storage barrels with tight-fitting lids, to protect it from insects and rodents. If you have barn-cats and therefore are not concerned about rodents, you can place grain anywhere the horses can't access it. This is incredibly important because, if a horse were to gain access to a grain room, he would binge on feed, most likely colic and possibly even die. When grain bins are stored outside or in a garage, you may need to install a locking latch to keep raccoons and bears out. If your barn floor is dirt, it is important to use pallets to keep the bags of grain off the cool, moist ground. Another option is to build a large wooden feed bin directly against a wall, to store loose/bagged/barreled grain as well as scoops and buckets.

Tips:

- Slanting the lids of a self-built feed bin is a helpful trick for discouraging people from placing items on top of it and making feed access more difficult.

- Buying a surplus of small buckets and pre-dishing both morning and evening grain for each horse can help make feeding more efficient, especially if you have new or inconsistent workers.

- High starch foods have been linked to exuberant behavior in some horses.

- Some veterinarians recommend feeding beet pulp and oil for necessary additional caloric intake instead of grains, which usually have a high glycemic index and can therefore increase your horse's risk of developing laminitis (Eades, 2010).

|

|

How much should I feed my horse?

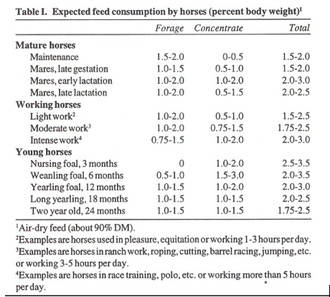

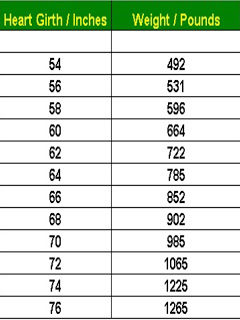

How much feed your horse requires depends on the quality/type of feed as well as the individual horse's size, condition and activity level. Most horses do not need to be fed grain. Grain is supplemental and should be saved for young/growing horses, breeding stallions, pregnant or lactating mares, hard-working horses and old horses that have a harder time keeping weight on. Feed by weight not number of flakes or volume of grain, as that is the most effective way of measuring/meeting a horse's dietary needs. Not to mention, hay flakes can range enormously in size! Vitamins rarely have to be supplemented if you are feeding good quality hay and trace mineral salt blocks will provide any needed minerals. There are two ways to calculate a horse's weight: walking them onto a scale, or using a measuring tape. There are also pre-calculated "weight tapes" specifically made for horses that measure the circumference of their barrel, starting behind their elbows and running at a slightly diagonal line up and over the lowest point of their withers (refer to the "Heart Girth vs Weight Chart").

|

Special Considerations:

Broodmares:

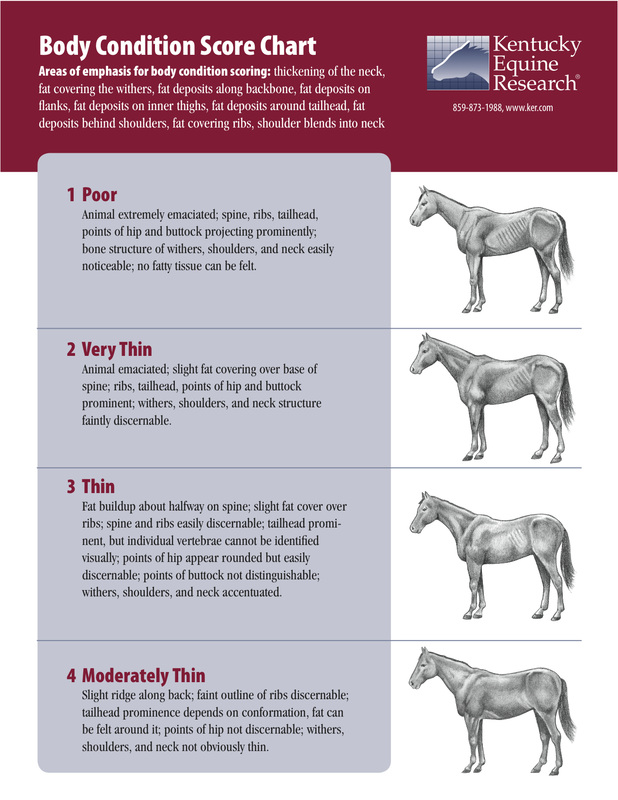

Early Gestation: The nutritional requirements of barren mares and those in early pregnancy are the same as for the maintenance of a mature horse. The fetus grows very slowly during this time, so the mare's diet can usually remain the same. It is important to monitor her intake and body condition so that she does not gain too much weight. The ideal body weight score at this time is between a 5 and 6. Broodmares that are too thin, tend to have lower pregnancy rates, longer gestation cycles, and decreased milk production. On the other hand, overweight mares have been shown to have no advantage in pregnancy or foaling rates over mares at a healthy weight (so they're doubling your feed bill for nothing) and have an increased risk of developing laminitis (Larson, 2012).

Mid Gestation: The mare's nutritional requirements begin increasing during the fifth month of pregnancy. The National Research Council recommends increasing her energy intake by 5-8%. However, access to good quality hay or grass is usually adequate. If supplementation is necessary, a fortified broodmare feed will provide additional energy and protein. For easy keepers, a ration balancer should meet these requirements.

Late Gestation: Fetal growth increases significantly at the eighth month and therefore, so do the mare's nutritional requirements. Good quality forage should still be the basis of her diet. However, supplementing with a 13-15% protein feed is recommended. It is also very important to increase the mare's mineral intake, specifically calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and copper, during this time (Pagan, 2010). If the mare is grazing on good quality pasture, she should be receiving adequate vitamin intake. If, however, she is stalled and consuming primarily hay, then she may need vitamins A, D, and E supplemented. Peter Huntington, director of equine nutrition of Kentucky Equine Research Australia, discussed one study that showed supplementing a mare's diet with 500 grams of soybean meal (a quality source of protein) two weeks prior to foaling and 750 grams of soybean meal 7 weeks after foaling increased the mare's milk crude protein content and increased foal growth rate. This is so important because most of the unborn foal's mineral retention occurs during the tenth month (Gibbs, 2000).

Lactating: Lactating mares have the highest nutritional needs out of any horse, racehorses in heavy training aside. They should be provided with high quality forage, as well as an energy-dense feed formulated specifically for lactating mares. If additional calories are needed, oil or rice bran can be added. In addition to having her energy needs nearly double during this time, it is important to realize that your mare's water consumption increases drastically too.

Stallions:

A breeding stallion's energy requirements depend heavily on how many mares they are covering. However, they usually require 25% more feed than during the off-season. Monitor your stallion's Body Condition Score (BCS) regularly to ensure he does not become overweight, because obesity has been shown to decrease both a stallion's libido and fertility (Kane, 2008). Semen lipids are thought to 'play a major role in motion characteristics, sensitivity to cold shock (loss of viability of cooled- stored and frozen semen) and fertilizing capacity of sperm," says Steven P. Brinsko, DVM, MS, PhD, Dipl. ACT, associate professor and chief of theriogenology at Texas A&M's Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. Brinsko suggests supplementing omega-3 fatty acids to improve a stallions fertility, by enhancing tissue levels of DHA (docosahexaenoic acid).

Foals:

For the first 6-8 weeks of life, foals are primarily supported by the dams milk. Creep feeding may be added within the first 10 weeks and has been shown to reduce weaning stress (NRC, 2001). Orphaned foals under the age of 10 weeks should be maintained on a "nurse-mare" or milk replacement. If cow's milk is used, it should be 2 percent skimmed and have 20g/L of dextrose added (Kane, 2007). Older foals can be weaned and maintained on creep feed and high-quality forage.

Seniors:

Horses over the age of 20 are generally considered to require special dietary considerations. The risk of dental disease increases with age and is thought to reduce a horse's ability to chew and digest, often leading to a decreased BCS. It has been suggested that senior horses' nutrient absorption and digestion is decreased, including Ca:P levels, but further research is needed (NRC, 2001).

Hot/Cold Weather:

In the winter, feeding and management practices must be adjusted to ensure adequate digestible energy intake and prevention of heat loss. The National Research Council and Committee of Nutrient Requirements of Horses advises increasing digestible energy by 2.5 percent for each degree Celsius below the lower critical temperature (NRC, 2001). It addition, it is recommended that horses be blanketed and provided with shelter to keep warm. Hot weather, however, requires a significant increase in water intake so both water and mineralized salt should be made accessible at all times.

Sport/Show Horse:

This is another important example of horses who require specific dietary considerations. In fact, a significant percentage of tested dressage and eventing horses have come up deficient in vitamin E, sodium, and other minor minerals (Marcella, 2010). A horse's nutritional needs can vary enormously between disciplines and should therefore be determined on an individual basis. Elizabeth Owens, consulting nutritionist to the Australian Equestrian Team which continues to dominate international three-day eventing competitions, found that "eventing horses consumed an average of between 1.48 and 2.45 percent of their body weight, dressage horses consumed between 1.04 and 1.79 percent, while show jumpers consumed between 1.09 and 2.55 percent". This is significant because it demonstrates that horses from different disciplines have different nutritional requirements and necessary daily feed intakes for proper maintenance and optimal performance.

Early Gestation: The nutritional requirements of barren mares and those in early pregnancy are the same as for the maintenance of a mature horse. The fetus grows very slowly during this time, so the mare's diet can usually remain the same. It is important to monitor her intake and body condition so that she does not gain too much weight. The ideal body weight score at this time is between a 5 and 6. Broodmares that are too thin, tend to have lower pregnancy rates, longer gestation cycles, and decreased milk production. On the other hand, overweight mares have been shown to have no advantage in pregnancy or foaling rates over mares at a healthy weight (so they're doubling your feed bill for nothing) and have an increased risk of developing laminitis (Larson, 2012).

Mid Gestation: The mare's nutritional requirements begin increasing during the fifth month of pregnancy. The National Research Council recommends increasing her energy intake by 5-8%. However, access to good quality hay or grass is usually adequate. If supplementation is necessary, a fortified broodmare feed will provide additional energy and protein. For easy keepers, a ration balancer should meet these requirements.

Late Gestation: Fetal growth increases significantly at the eighth month and therefore, so do the mare's nutritional requirements. Good quality forage should still be the basis of her diet. However, supplementing with a 13-15% protein feed is recommended. It is also very important to increase the mare's mineral intake, specifically calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and copper, during this time (Pagan, 2010). If the mare is grazing on good quality pasture, she should be receiving adequate vitamin intake. If, however, she is stalled and consuming primarily hay, then she may need vitamins A, D, and E supplemented. Peter Huntington, director of equine nutrition of Kentucky Equine Research Australia, discussed one study that showed supplementing a mare's diet with 500 grams of soybean meal (a quality source of protein) two weeks prior to foaling and 750 grams of soybean meal 7 weeks after foaling increased the mare's milk crude protein content and increased foal growth rate. This is so important because most of the unborn foal's mineral retention occurs during the tenth month (Gibbs, 2000).

Lactating: Lactating mares have the highest nutritional needs out of any horse, racehorses in heavy training aside. They should be provided with high quality forage, as well as an energy-dense feed formulated specifically for lactating mares. If additional calories are needed, oil or rice bran can be added. In addition to having her energy needs nearly double during this time, it is important to realize that your mare's water consumption increases drastically too.

Stallions:

A breeding stallion's energy requirements depend heavily on how many mares they are covering. However, they usually require 25% more feed than during the off-season. Monitor your stallion's Body Condition Score (BCS) regularly to ensure he does not become overweight, because obesity has been shown to decrease both a stallion's libido and fertility (Kane, 2008). Semen lipids are thought to 'play a major role in motion characteristics, sensitivity to cold shock (loss of viability of cooled- stored and frozen semen) and fertilizing capacity of sperm," says Steven P. Brinsko, DVM, MS, PhD, Dipl. ACT, associate professor and chief of theriogenology at Texas A&M's Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. Brinsko suggests supplementing omega-3 fatty acids to improve a stallions fertility, by enhancing tissue levels of DHA (docosahexaenoic acid).

Foals:

For the first 6-8 weeks of life, foals are primarily supported by the dams milk. Creep feeding may be added within the first 10 weeks and has been shown to reduce weaning stress (NRC, 2001). Orphaned foals under the age of 10 weeks should be maintained on a "nurse-mare" or milk replacement. If cow's milk is used, it should be 2 percent skimmed and have 20g/L of dextrose added (Kane, 2007). Older foals can be weaned and maintained on creep feed and high-quality forage.

Seniors:

Horses over the age of 20 are generally considered to require special dietary considerations. The risk of dental disease increases with age and is thought to reduce a horse's ability to chew and digest, often leading to a decreased BCS. It has been suggested that senior horses' nutrient absorption and digestion is decreased, including Ca:P levels, but further research is needed (NRC, 2001).

Hot/Cold Weather:

In the winter, feeding and management practices must be adjusted to ensure adequate digestible energy intake and prevention of heat loss. The National Research Council and Committee of Nutrient Requirements of Horses advises increasing digestible energy by 2.5 percent for each degree Celsius below the lower critical temperature (NRC, 2001). It addition, it is recommended that horses be blanketed and provided with shelter to keep warm. Hot weather, however, requires a significant increase in water intake so both water and mineralized salt should be made accessible at all times.

Sport/Show Horse:

This is another important example of horses who require specific dietary considerations. In fact, a significant percentage of tested dressage and eventing horses have come up deficient in vitamin E, sodium, and other minor minerals (Marcella, 2010). A horse's nutritional needs can vary enormously between disciplines and should therefore be determined on an individual basis. Elizabeth Owens, consulting nutritionist to the Australian Equestrian Team which continues to dominate international three-day eventing competitions, found that "eventing horses consumed an average of between 1.48 and 2.45 percent of their body weight, dressage horses consumed between 1.04 and 1.79 percent, while show jumpers consumed between 1.09 and 2.55 percent". This is significant because it demonstrates that horses from different disciplines have different nutritional requirements and necessary daily feed intakes for proper maintenance and optimal performance.

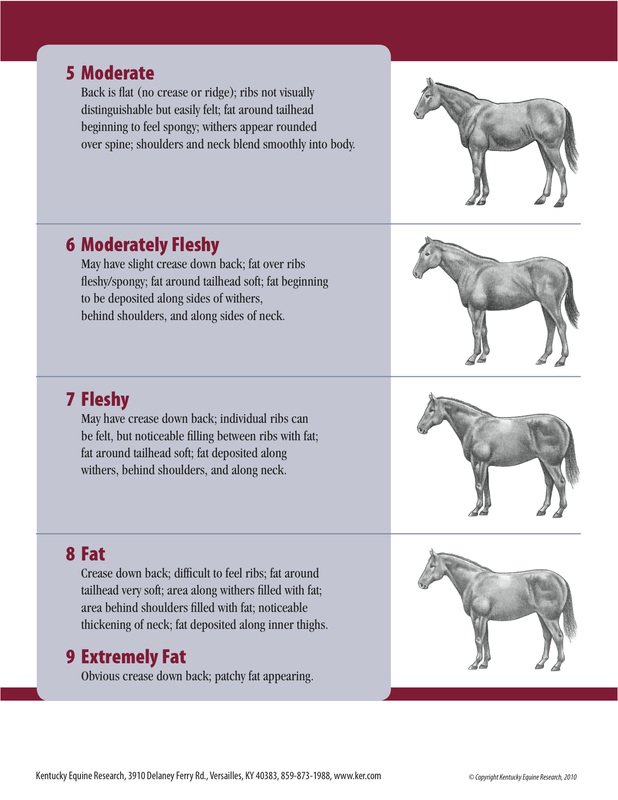

Determining your horse's Body Condition Score:

|

|||||||