Thermoregulation in the Horse

Horses are homeothermic animals, also known as warm-blooded, meaning that they maintain a stable internal body temperature regardless of external influences. However, this requires a proper balance of heat production and loss. In the wild, horses sweat and may seek shade or even wade into cooler water. On the other hand, when a wild horse is cold they may seek escape from the wind, shiver, and huddle together for warmth. Most importantly though, horses are naturally designed to keep moving and grazing, which provides a constant feed intake and therefore heat production. These thermoregulating behaviors are things that many domestic horses do not have available to them, as they are commonly turned out alone in small grass-free and sometime even tree/shelter-free paddocks and then confined to a stall throughout the night. These changes in environment require that management of domestic horses consider their methods of thermoregulation.

Read More...

Horses have a relatively wide thermoneutral zone, due to their well-insulated coats and large body mass compared to surface area (Cena and Clark, 1979), the lower limit of which is referred to as the lower critical temperature (LCT). The LCT is defined as "below this limit the metabolic rate must increase if deep body temperature is to be maintained (Morgan, 1998 and Mount, 1973). In multiple published works on the topic, Karin Morgan found the thermoneutral zone for horses to be between 5-25°C (approximately 40-80°F). This range is consistent with Young and Coote's 1973 study which revealed the LCT in young and indoor horses to be around 5°C. The LCT can vary, however, depending on the horse breed, age and living conditions/ability to acclimate. For example, McBride et. al measured the thermoneutral zone for mature quarter horse geldings living outdoors and found the LCT to be -15°C.

Granted it is easier for horses to warm up than to cool down, it is still important that we consider their increased metabolic needs and naturally evolved coat in the winter. A horse's total insulation is provided by three thermal layers: the peripheral body tissue, the coat and the boundary layer of the air (McArthur, 1981). Although skin thickness and snow on the horse's back can both provide a degree of insulation, the more influential and also easiest to influence is the horse's coat. That being said, the "boundary layer of air" is important to consider because wearing a blanket flattens a horse's hairs, preventing them from standing up and trapping that insulating layer of warm air. So putting a "weightless" blanket on your horse in cool weather can actually cause more harm than good. These thin blankets can still be beneficial for keeping your horse clean and dry and may add some insulation benefit if coupled with a fleece under-layer (such as a cooler or stable blanket), but it is best to use a "medium" or "heavyweight" blanket if you use one at all.

Coat insulation depends on the depth and thickness of the hair layer, which can vary between horse breeds and depend on the individual's opportunity to acclimate, as well as wind speed, temperature and humidity (Ousey, 1992). A horse's coat changes with the seasons due to differences in environmental temperature as well as a mechanism called photoperiodism, which relies on sensors in the horses skin that react to changes in daytime light length. In addition, horses engage hair erector muscles (known as piloerection) in order to raise, lower and turn hairs in the coat. This has been shown to increase coat depth by 10-30% in mature horses (Young, 1973). However, these erector muscles must be exercised regularly in order to work properly. This means that blanketing your horse too early or too often can actually impair their naturally ability to tolerate the cold. Without exposure to cooling temperatures and a chance to acclimate, horses are unlikely to grow a thick coat. If they are always stabled and blanketed, they lack the necessary stimuli to trigger thermoregulatory mechanisms (such as erector muscles). In addition, a blanketed horse often tries to warm their exposed areas (head, neck, belly, and legs) and can therefore become overheated underneath the blanket. A horse is unable to heat up selected areas of their body. Either their whole body cools down or their whole body heats up. The risk with this, is that an overheated blanketed horse can end up sweating which can actually result in making them even colder and more susceptible to illness. As a result, it is advisable only to blanket a horse during extreme temperature lows (below their LCT).

There are, however, instances when more regular blanketing is necessary. Many horse owners prefer to clip the coats of horses who will maintain a heavy and regular workload throughout the winter, as a thick coat can cause them to overheat and negatively impact their recovery from exercise. A 2012 Swedish study which examined horses' temperature regulation during exercise and recovery in a cool environment concluded that, provided clipped horses began workouts with a blanket or quarter sheet (otherwise their leg temperatures dropped at the onset of exercise and took 30 minutes to increase), they had an advantage over unclipped horses whose overheating was evident by their respiratory rate and elevated rectal temperature (Hannah, 2014). If you do decide to clip your horse, it is extremely important to blanket them any time they are exposed to the cold. Seniors, foals, and sick horses also commonly need to be blanketed in conditions other mature horses could tolerate and even benefit from. Also consider your horse's breed. For example, many Thoroughbreds have a higher LCT due to a thin coat and fast metabolism.

Horses have a relatively wide thermoneutral zone, due to their well-insulated coats and large body mass compared to surface area (Cena and Clark, 1979), the lower limit of which is referred to as the lower critical temperature (LCT). The LCT is defined as "below this limit the metabolic rate must increase if deep body temperature is to be maintained (Morgan, 1998 and Mount, 1973). In multiple published works on the topic, Karin Morgan found the thermoneutral zone for horses to be between 5-25°C (approximately 40-80°F). This range is consistent with Young and Coote's 1973 study which revealed the LCT in young and indoor horses to be around 5°C. The LCT can vary, however, depending on the horse breed, age and living conditions/ability to acclimate. For example, McBride et. al measured the thermoneutral zone for mature quarter horse geldings living outdoors and found the LCT to be -15°C.

Granted it is easier for horses to warm up than to cool down, it is still important that we consider their increased metabolic needs and naturally evolved coat in the winter. A horse's total insulation is provided by three thermal layers: the peripheral body tissue, the coat and the boundary layer of the air (McArthur, 1981). Although skin thickness and snow on the horse's back can both provide a degree of insulation, the more influential and also easiest to influence is the horse's coat. That being said, the "boundary layer of air" is important to consider because wearing a blanket flattens a horse's hairs, preventing them from standing up and trapping that insulating layer of warm air. So putting a "weightless" blanket on your horse in cool weather can actually cause more harm than good. These thin blankets can still be beneficial for keeping your horse clean and dry and may add some insulation benefit if coupled with a fleece under-layer (such as a cooler or stable blanket), but it is best to use a "medium" or "heavyweight" blanket if you use one at all.

Coat insulation depends on the depth and thickness of the hair layer, which can vary between horse breeds and depend on the individual's opportunity to acclimate, as well as wind speed, temperature and humidity (Ousey, 1992). A horse's coat changes with the seasons due to differences in environmental temperature as well as a mechanism called photoperiodism, which relies on sensors in the horses skin that react to changes in daytime light length. In addition, horses engage hair erector muscles (known as piloerection) in order to raise, lower and turn hairs in the coat. This has been shown to increase coat depth by 10-30% in mature horses (Young, 1973). However, these erector muscles must be exercised regularly in order to work properly. This means that blanketing your horse too early or too often can actually impair their naturally ability to tolerate the cold. Without exposure to cooling temperatures and a chance to acclimate, horses are unlikely to grow a thick coat. If they are always stabled and blanketed, they lack the necessary stimuli to trigger thermoregulatory mechanisms (such as erector muscles). In addition, a blanketed horse often tries to warm their exposed areas (head, neck, belly, and legs) and can therefore become overheated underneath the blanket. A horse is unable to heat up selected areas of their body. Either their whole body cools down or their whole body heats up. The risk with this, is that an overheated blanketed horse can end up sweating which can actually result in making them even colder and more susceptible to illness. As a result, it is advisable only to blanket a horse during extreme temperature lows (below their LCT).

There are, however, instances when more regular blanketing is necessary. Many horse owners prefer to clip the coats of horses who will maintain a heavy and regular workload throughout the winter, as a thick coat can cause them to overheat and negatively impact their recovery from exercise. A 2012 Swedish study which examined horses' temperature regulation during exercise and recovery in a cool environment concluded that, provided clipped horses began workouts with a blanket or quarter sheet (otherwise their leg temperatures dropped at the onset of exercise and took 30 minutes to increase), they had an advantage over unclipped horses whose overheating was evident by their respiratory rate and elevated rectal temperature (Hannah, 2014). If you do decide to clip your horse, it is extremely important to blanket them any time they are exposed to the cold. Seniors, foals, and sick horses also commonly need to be blanketed in conditions other mature horses could tolerate and even benefit from. Also consider your horse's breed. For example, many Thoroughbreds have a higher LCT due to a thin coat and fast metabolism.

|

Blanket Fit and Measurement

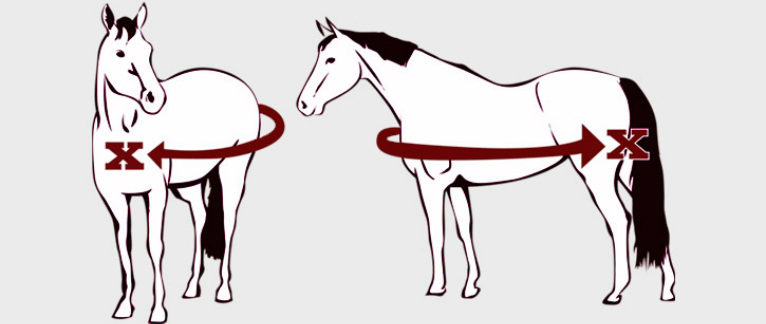

Measuring your horse's blanket size:

- Stand your horse squarely on a hard, flat surface.

- Hold one end of the measuring tape against the horse's chest and run it around the shoulder, barrel, widest part of the hindquarter, and end to the side of the tail.

- The number of inches measured equals your horse's blanket size (for example, if you measure 74 inches your horse wears a blanket size 74). If necessary or when in doubt, round up.

Checking blanket fit:

- Stand behind the horse, bringing the two ends of the blanket together. If they overlap or meet on the horses tail, the blanket is too large. If there are more than 3 inches of exposed rump on either side of the tail, the blanket is too small.

- Now stand in front of the horse, watching his/her movement as they walk. If the blanket drops low at the chest or shoulder, it is most likely too large. If the fabric pulls tightly against the shoulder, it is likely impeding movement and therefore too small.

- The blanket should drop past the belly but should not go more than halfway to the horse's hocks.

- Also, a study which measured pressure points and sores caused by blanket use, found that blankets with a V-shaped insert (as opposed to a straight cut or cut-back withers) placed significantly less pressure on the horse's withers (Hilary, 2010).

How should the blanket be worn?

An incorrectly fitted blanket can be dangerous for the horse and often results in discomfort. If a blanket is too tight, it will rub and cause sore/raw spots. If the blanket is too large, it can twist when they roll and run, potentially causing them to step on it and trip or entangle themselves. If straps are not adjusted properly, a horse can get a leg stuck in a loose hanging strap or have raw spots from them being secured too tightly.

|

Chest Straps

There should be some fabric overlap beneath the front buckles and the blanket shouldn't be too tight or loose across the shoulders. |

Surcingle

If there is just a single strap, bring it under the horse's belly like a girth and connect it on the other side. If there are two straps, they should cross under the horse before being fastened. In either regard, surcingles should be adjusted with a hand's width between the strap and horse's belly. TIP: You can buy a single surcingle strap that runs around the horses whole barrel (over their withers and back under their belly). This can be used in place of a broken strap or to enable a horse to wear a slightly too large blanket.

|

Leg Straps

Leg straps should also be crossed before connected. So the right leg strap would go between the horse's rear legs before connecting to the left D-ring. These should be tightened to allow approximately 4 inches of room between the strap and horse's inner thigh. |

Types of Horse Blankets

Turnout RugsTurnout rugs or blankets are light-weight, often-times water-proofed sheets, designed to withstand turn-out conditions and rough horseplay. They are usually made of rugged fabric with a poly/cotton mesh lining, and have pleats/gussets at the shoulder and haunches to allow ease of movement. These blankets would be too warm for use during the Summer and do not provide enough protection in the Winter. As a result, they are used primarily in the Fall to protect the horse from wet weather and mud in cool temperatures. It should be noted that turn-out rugs, like any sheet without fill, can impair a horse's natural ability to stay warm by forcing their hair to lie flat and preventing the circulation of body heat. In addition, this blanket type is often water-resistant and not truly water-proof. Therefore they should be used under supervision, to ensure the horse isn't stuck wearing a wet rug, too cold or sweating without proper ventilation.

|

Winter BlanketsWinter blankets come in light-weight (100 grams), mid-weight (180-200 grams) and heavy-weight (300-440 grams), depending on the amount of poly fill between the outer and inner layers. The fill, measured in grams, adds warmth and helps insulate the horse's body heat. Choosing the right weight blanket for your horse can be difficult, as every horse's needs vary. Each horse, like people, can run a little warmer or cooler than the average. Age and breed can also affect their blanketing needs. A hot-blooded, thing-haired Thoroughbred often requires a blanket three seasons, while a healthy and young Morgan will usually grow a good enough coat to never need one at all. When in doubt, buy a medium-weight blanket because heavy-weights are often too much for a horse, especially on a sunny day, and light-weights may not be enough in frigid winter temps, especially for a body clipped horse.

|

Stable BlanketsStable blankets come in a wide range of weights, similarly to winter blankets. They are usually quilted and, while not water-proof, many are moisture-resistant to guard against urine and manure stains. Stable blankets are more fitted than turn-out rugs and therefore restrict the horse's movement. The use of a stable blanket allows you to replace a heavy-weight, wet and soiled turn-out rug with a warm and clean blanket to keep your horse warm while he's stalled.

|

Rain SheetsRain sheets are made of waterproof fabric. Some heavy duty waterproof sheets with inner cotton layers can be found for turn-out in wet conditions, but mostly these sheets have minimal fastenings and are used to keep your horse and tack dry when walking him from one location to another during inclement weather.

|

Anti-Sweat SheetsAnti-sweat sheets are made of cotton or cotton blend mesh. They are placed on a sweaty or freshly bathed horse to help wick the moisture away and keep chill away while they dry. The holes in the mesh allow hot air from the horses's body to escape. It is important to monitor the use of anti-sweat sheets, as their fibers can becomes saturated if the horse is extremely wet. In this instance, a fresh sheet should be place on them until they are completely dry.

|

CoolersCoolers are similar to anti-sweat sheets, in their use in keeping a horse warm while he dries. Coolers usually cover the horse's entire body, provide better protection from drafts and are generally used in colder conditions. A cooler is ready to be removed when you see a dew-like coating forming on the top surface. A very wet or sweaty horse may require two changes before they are dry.

|

Other Types of Horse Blankets

There are many other blanket types available that are less commonly used. For example: dress sheets to keep your horse comfortable during transport and clean before a show, expensive therapeutic blankets with nano-fibers and magnets to help relax and sooth muscles, fly sheets to keep the bugs away, and quarter sheets for use while lunging or riding to prevent chills and muscle stiffness while warming up/cooling down.